FUNCTIONAL SCAPULOTHORACIC ABNORMAL MOTION (STAM)

Overview

For patients in Richmond, VA seeking specialized care, understanding the mechanics of functional scapulothoracic abnormal motion (STAM) is the first step toward recovery. Scapulothoracic Abnormal Motion (STAM), widely referred to as scapular dyskinesis, is defined as a problem in which the scapula (shoulderblade) fails to maintain normal anatomic position or movement patterns during shoulder motion.

The scapula is a thin bone on our back. The part of it furthest lateral (away from our midline) is made up of important components such as the glenoid (the socket of the shoulder), the acromion (the roof of the shoulder that can be felt through our skin) and the coracoid process (a small bony prominence on the front of our shoulder.

When we need to move our arm, the scapula needs to move as well. We achieve far more range of motion when you add “scapulothoracic” motion to the motion that we can get just purely through the shoulder ball and socket joint. Our brain normally controls this process seamlessly by telling certain scapular muscles to fire and other muscles to relax. However, when this cannot occur properly, our scapula ends up in the wrong place (hence “abnormal motion”). With our scapula in the wrong place, our humerus (arm bone) might start hitting some of the bony structures around the shoulder (like the acromion, part of the scapula and therefore no longer in the right place), and we lose motion as a result. Alternatively, with our scapula in the wrong place, some of our muscles might have an excessively challenging time controlling our arm and the same sort of disability might result.

There are two main categories of STAM: Structural STAM and Functional STAM.

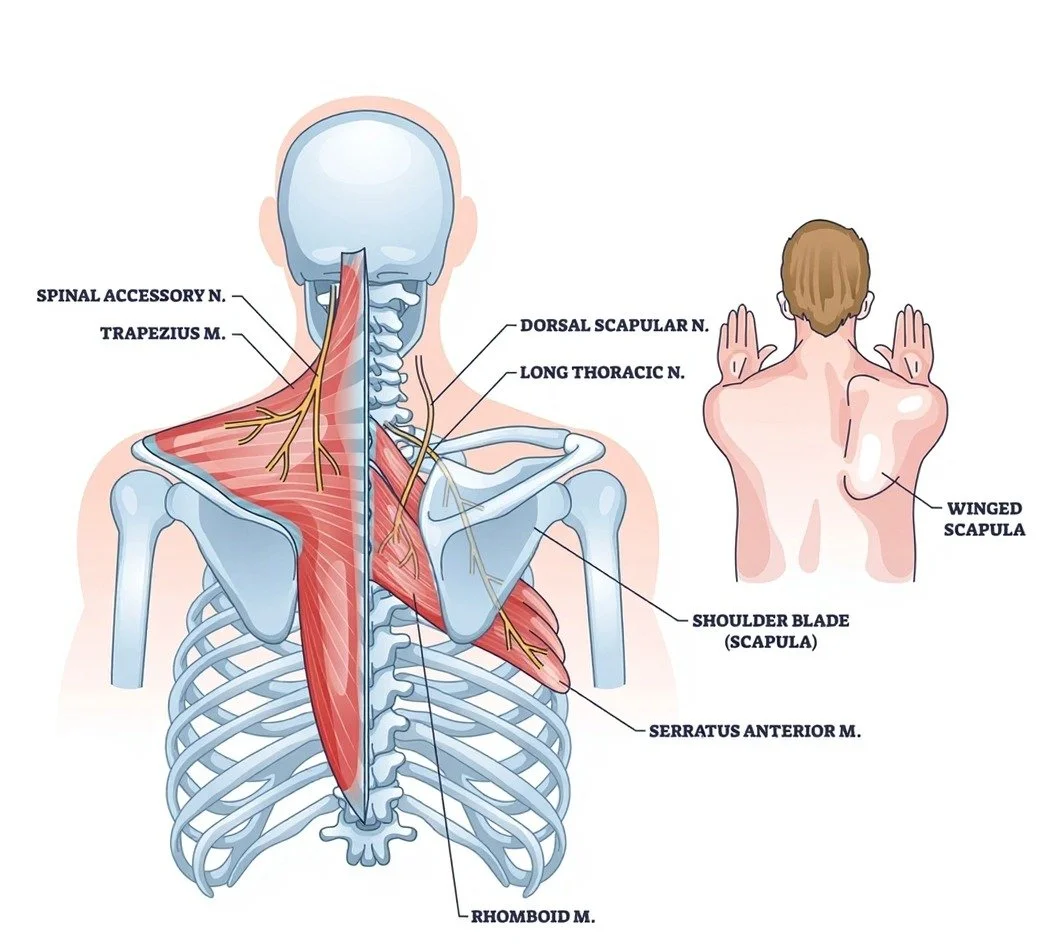

Structural STAM: Resulting from identifiable anatomic pathology, such as nerve injury (paralysis), bony deformity, or tendon rupture.

Functional STAM (fSTAM): Resulting from a neuromuscular coordination disorder. In these patients, the gross anatomy is intact—the nerves conduct signals and the bones are normal—but the motor firing patterns are dysregulated. This typically presents as an imbalance between a hyperactive pectoralis minor and a hypoactive serratus anterior.

Understanding the scapula’s mechanics is challenging. Many muscles attach to it and the scapula moves in multiple planes at once, on our curved chest wall. It’s a complex three-dimensional concept. At it’s most simple, we can think about the hyperactive pectoralis minor tilting the scapula (via its coracoid) forward. When the scapula tilts forward, the roof of the scapula (the acromion) tilts forward with it. When someone with this problem tries to raise their arm, it could hit the acromion before it gets fully raised. Normally, the serratus anterior, by pulling bottom of the scapula back onto the chest wall, should counteract this anterior tilt. But in worse versions functional STAM, the serratus is hypoactive and doesn’t do this job as well. Seeing the scapula wing in the back will be more apparent and raising the arm will be even more challenging.

When the scapula doesn’t move appropriately, other adjacent structures often become affected and patients may develop: rotator cuff tears, biceps tendonitis or SLAP tears, shoulder impingement and bursitis and labral tears and shoulder instability.

For more information on this topic, see the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeon's educational page here.

Video courtesy of 3D Anatomy Lyon

Video courtesy of 3D Anatomy Lyon

The Classification (fSTAM Subtypes)

Treatment is guided by the specific pattern of neuromuscular dysregulation:

fSTAM 1: Pectoralis Minor Hyperactivity

This is often also called Pectoralis Minor Syndrome and signficantly overlaps with Thoracic Outlet Syndrome but expert evaluation is necessary to determine which is the most appropriate diagnosis

Cause: Characterized primarily by hyperactivity of the pectoralis minor. There is also some hyperactivity of the upper trapezius (which might then be painful) and some hypoactivity of the serratus anterior. When the pectoralis minor has been hyperactive for a long time it can start to shorten.

Clinical Presentation: Patients have exquisite tenderness over the pectoralis minor insertion on the coracoid. The scapula might rest in an anteriorly tilted position. When raising and lowering the arm, the bottom corner of the scapula might become prominent. This can be very subtle. Patients occasionally present with neurological symptoms (numbness or tingling in the hand) due to brachial plexus compression under the tight pectoralis minor.

fSTAM 2: Serratus Anterior Hypoactivity

Cause: Similar to fSTAM1 in the sense that the pectoralis minor remains hyperactive but now the serratus anterior is even more hypoactive, becoming worse at its job of keeping the scapula on the chest wall. There is more obvious winging of the scapula in these patients and patients have lost the ability to fully raise their arm.

Subtype 2A (Reducible): The winging and limitation in raising the arm can be corrected by the examiner manually assisting the scapula (Scapular Assistance/Compression Tests).

Subtype 2B (Irreducible): The scapula’s incorrect position is severe and hard to move; the scapula cannot be fully repositioned manually by an examiner.

fSTAM 3: Dystonic / Global Hyperactivity

Cause: A severe, fixed deformity caused by simultaneous hyperactivity of all periscapular muscles (Pectoralis Minor, Rhomboids, Levator Scapulae, Upper Trapezius).

Clinical Presentation: The scapula is elevated and protracted in a rigid, non-anatomic position. Range of motion is severely limited.

fSTAM 4: Scapular Myoclonus ("The Dancing Scapula")

Cause: Characterized by rhythmic, involuntary muscle depolarizations.

Subtype 4A: Occurs at rest.

Subtype 4B: Induced by sensory or motor stimulus.

Diagnosis & Evaluation

Differentiation between Functional (neuromuscular) and Structural (nerve injury) STAM is the most critical step in determining the plan of care.

Clinical Examination

Coracoid Tenderness: Patients with pectoralis minor problems are often very tender directly over the coracoid where this muscle attaches.

Strength Testing: Each muscle around the scapula that can cause problems can be tested in isolation.

Shoulder Flexion Resistance Test (SFRT): The patient flexes the arm against resistance. If the scapula remains stable or the patient can generate force despite winging, the long thoracic nerve is likely intact (ruling out serratus anterior paralysis).

Scapular Assistance/Compression Tests: The examiner manually stabilizes the scapula during elevation. Symptom resolution confirms a functional, reducible problem.

Additional Tests

Depending on a patient’s history and exam, more tests might be ordered such as:

X-ray of the shoulder

MRI of the shoulder

MRI of the brachial plexus (all the nerves living next to your shoulder that go down to your arm)

Electromyography (EMG) - a test used to evaluate for any nerve injury

Non-Operative Management

Primary management for Functional STAM is non-surgical.

Neuromuscular Re-education (Physical Therapy): A specialized protocol focusing on motor control rather than simple strengthening. The goal is to stretch the hyperactive and shortened pectoralis minor while recruiting the hypoactive serratus anterior.

Temporary Pectoralis Minor Paralysis (Botox): For cases that don’t improve with simple stretching, Botox (botulinum toxin) canb be injected by a radiologist into the pectoralis minor. This creates a temporary paralysis of the hyperactive muscle, creating a "window of opportunity" for physical therapy to stretch it and retrain the other scapula stabilizer muscles without the pectoralis minor’s hyperactivity.

External Neuromodulation: Use of surface EMG biofeedback or stimulation to aid in the recruitment of the hypoactive muscle groups.

Surgical Solutions

Surgery is reserved for refractory cases where nonoperative treatments have failed to restore function after 6-12 months.

Arthroscopic Pectoralis Minor Release

Indication: Failed nonoperative management in fSTAM 1

Technique: An arthroscopic (minimally invasive) procedure to cut the pectoralis minor tendon off the coracoid to permanently eliminate the anterior tilting force.

Scapulopexy + Pectoralis Minor Release

Indication: Failed nonoperative management in fSTAM 2A and B

Technique: The scapula is physically tethered to the rib cage using a tendon graft. This limits winging, provides a stable anchor for rehabilitation, and theoretically helps retrain the brain to fire the scapular muscles correctly.

Indication: Bilateral fSTAM 2 or fSTAM 3 and 4

Technique: A semi-rigid connection is created between the midline borders of the left and right scapulae using an graft tendon. The contralateral healthy or stronger scapula provides dynamic stability to the affected side and helps the brain relearn

Indication: Cases of fSTAM that do not respond to nonoperative management and the above less-invasive surgeries

Technique: The scapula is permanently fused to the rib cage in the proper position so it can no longer wing and becomes less symptomatic. This is an invasive surgery that requires a high degree of expertise and caution.