Glenohumeral Arthritis (Shoulder Arthritis)

Overview

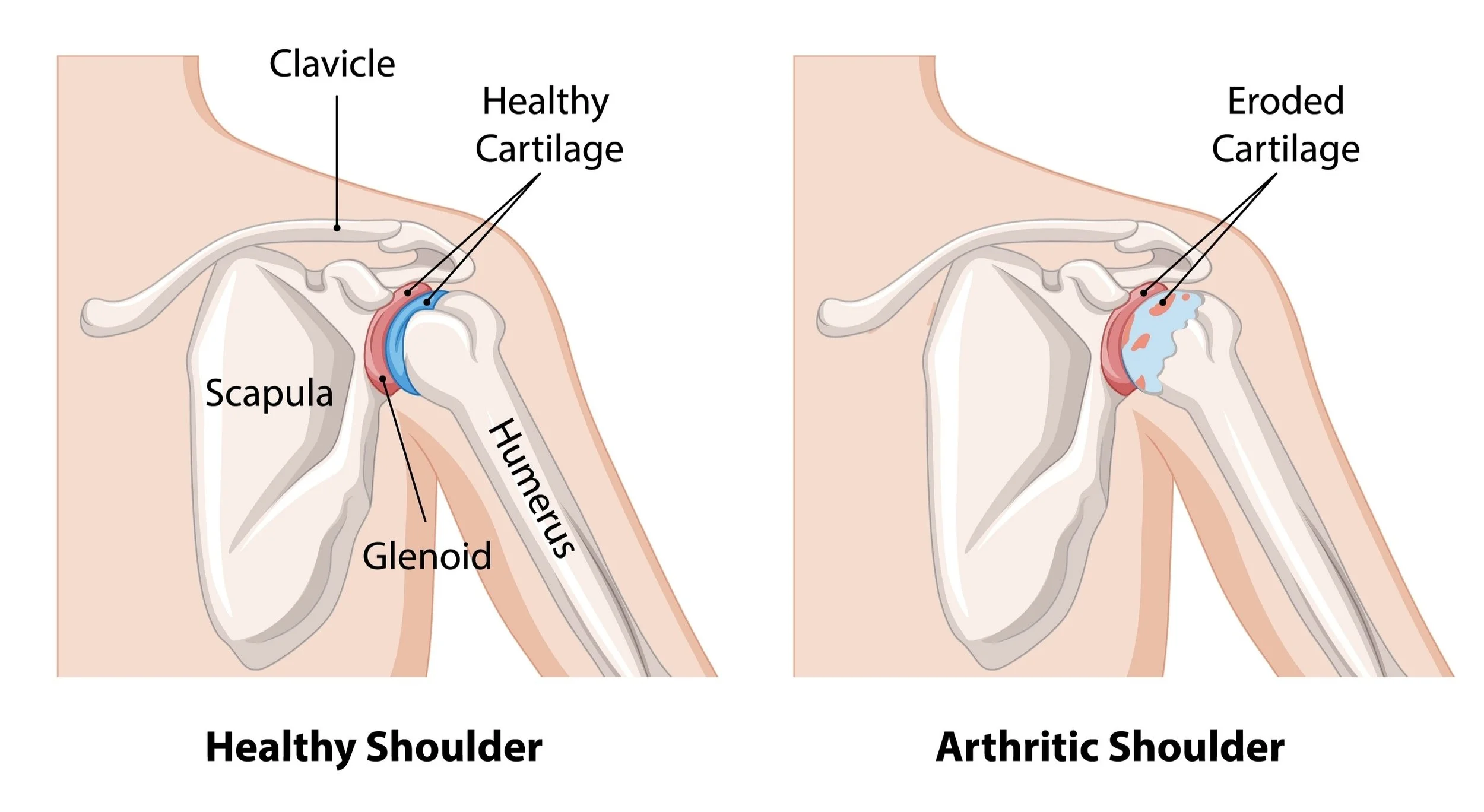

For patients in Richmond, VA seeking specialized care, understanding the mechanics of shoulder arthritis is the first step toward recovery. The shoulder is a ball-and-socket joint lined with a smooth substance called articular cartilage. This cartilage acts as an extremely low-friction coating, allowing the ball to glide easily on the socket. Osteoarthritis is the gradual wearing away of this protective cartilage layer. It often is bipolar, which means occurring on both sides of the joint - the humeral head (ball) and glenoid (socket).

As the cartilage thins, eventually, the underlying bone is exposed, leading to a "bone-on-bone" grinding sensation. The nerve endings that live in this exposed bone are a common cause for increased pain as arthritis progresses. The body responds to this cartilage loss by creating bone spurs (osteophytes) around the joint, and the surrounding tissues can get inflammed and tight. Unlike the hip or knee, shoulder arthritis can be fairly well tolerated until it reaches a critical tipping point of stiffness and pain. An important note about arthritis anywhere in the body: science does not yet have a way of regenerating lost cartilage - once arthritis begins, the cartilage loss will only continue to worsen. Symptoms may wax and wane but on a cellular level, the cartilage will never regrow.

Shoulder arthritis is most commonly diagnosed on x-ray, however additional imaging is often required (such as CT and MRI) to better characterize what is happening to the bone and soft tissue around the shoulder joint.

For more information on this topic, see the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeon's educational page here.

Symptoms

Deep Ache: A dull, persistent pain deep inside the joint, often felt in the back of the shoulder and worse at night.

Crepitus: A sensation of grinding, ratcheting, or clicking when moving the arm.

Loss of Motion: Difficulty with any motion but especially reaching behind the back (internal rotation) or reaching overhead.

Types of Shoulder Arthritis

Primary Osteoarthritis: Normal wear-and-tear that occurs without any other cause (genetic or age-related).

Post-Traumatic: Arthritis that develops in the months to years after a fracture or dislocation. During those injuries, the cartilage is damaged and the arthritis develops from there.

Cuff Tear Arthropathy: Arthritis caused by a long-standing rotator cuff tear (see Rotator Cuff Tears).

Avascular Necrosis: In this condition, the blood supply to the humeral head is compromised and the bone begins to die. It’s most commonly due to chronic steroid use but can also occur because of proximal humerus fractures and a variety of medical conditions.

Septic Arthritis: This term is a bit inaccurate. Septic arthritis is a spontaneous infection of any joint. It requires an urgent surgical washout but just by itself, it is not arthritis in the sense of cartilage loss. However, if left untreated for too long, the cartilage will die and true arthritis will eventually result prematurely.

Non-Operative Management

Cortisone Injections: A powerful anti-inflammatory delivered directly into the joint space to reduce pain, though it does not regrow cartilage.

Physical Therapy: Focusing on gentle range of motion to prevent the joint from freezing and to strengthen some of the adjacent weakened muscles.

Activity Modification: Avoiding heavy lifting or impact loading.

Medications: Non-opiate medications such as NSAIDs work like steroid injections to help reduce the pain.

When is Surgery Needed?

Surgery is a quality-of-life decision. When non-operative treatments have failed after weeks to months and a patient still has pain, difficulty sleeping and doing day-to-day or recreational activities then surgery may be discussed.

Surgical Solutions

Treatment for shoulder arthritis depends on a variety of factors including patient age, patient preference and if there is a rotator cuff tear. The most definitive treatment involves some form of arthroplasty, which is the medical term for joint replacement.

Comprehensive Arthroscopic Management - For very young patients with shoulder arthritis, this cleanout procedure may give them a few more years of relative pain relief.

Pyrocarbon Hemiarthroplasty - For younger patients with an intact rotator cuff, this relatively newer procedure replaces the humeral head (the ball) with a material called pyrocarbon that has similar properties to bone. The glenoid (socket) is not replaced. This helps eliminate socket replacement complications, and theoretically makes any future revision arthroplasty surgery perhaps easier.

Anatomic Total Shoulder Replacement – For patients with an intact rotator cuff, an anatomic replacement is a great option to replace the cartilage that is lost with metal and plastic. In this procedure, the ball is replaced with a ball, and the socket is replaced with a socket.

Reverse Shoulder Replacement – For patients with a rotator cuff tear or significant deformity of their socket, a reverse shoulder replacement is usually the best option. Unlike an anatomic replacement, in a reverse replacement the ball is replaced with a socket and the socket is replaced with a ball. This swap alters the physics of the shoulder joint and makes the deltoid muscle more effective at lifting the arm. This in turn removes the need for an intact rotator cuff, making this an excellent option for patients with signficant rotator cuff tears. There also is a growing trend for using reverse shoulder replacements even for patients without rotator cuff tears given how successfully they have been in improving patients’ pain and function.